2020-21 Playoff Push: Faceoffs, Power Plays, and Home Ice

Steve Kournianos | 4/21/2021 | [hupso]

NASHVILLE (The Draft Analyst) — Nobody likes a defeatist attitude, especially if you’ve been spending the last few months convincing yourself that the disappointment you call a hockey team is actually quite better than their record may indicate. And of course, you’re probably at the point of the season where you’ve memorized the seven or eight different scenarios where actually making the playoffs is quite reasonable. Stay positive, right?

And what about the Stanley Cup? Surely one can’t deny recent history, when mediocre regular-season squads like last season’s Dallas Stars or the San Jose Sharks in 2016 shocked the hockey world by slicing through favorites in each of the first three rounds to win the conference championship. Heck, wasn’t it the 2010 Philadelphia Flyers who needed to win their regular-season finale just to get into the postseason as the No. 8 seed before marching all the way the Stanley Cup Final?

Nonetheless, exceptions to the rule they most certainly are. Of the 60 different conference finalists since the introduction in 2005-06 of the “loser’s point” for overtime or shootout losses, 27 percent (16/60) finished the regular season with a sub-.600 points percentage, and only one — the 2012 Los Angeles Kings (.579) — went on the win the Stanley Cup. Of course, this is far from groundbreaking news — the teams with the higher points percentages dominate the field of 16, thereby increasing the likelihood they reach the postseason’s final four.

But what about the other regular-season factors that may indicate whether or not a team is either primed for a deep run at the Cup, or otherwise destined for a postseason flameout, if they even qualify? Does having a lethal power play help? What about faceoffs? And is there a deeper “advantage” to playing on home ice during the Stanley Cup Playoffs, especially now that fans are allowed to attend games and home teams win 53.1% of the time with crowds present.

As you’ll see below, we delve into some common talking points that surround teams who are looking to make this postseason last as long for them as possible.

“Faceoffs are killing us!”

Every trade deadline you always hear about the demand for “faceoff specialists” and for good reason — the prevailing belief around the NHL faceoff success translates to possession success, which in turn makes a team tougher to play against. Or is it?

Since the NHL began tracking the stat in the 1997-98 season, the average regular-season rank in faceoff success for conference finalists is 12th (out of 26 to 31 teams, depending on the year). It does, however, climb to 10th overall for Stanley Cup finalists and jumps to ninth for Stanley Cup winners. And if you omit the Sidney Crosby-driven Pittsburgh Penguins and their terrible faceoff numbers in the Cup-winning years of 2009 (30th), 2016 (14th), and 2017 (28th), the average postseason champion placed seventh in the league at the dot during their corresponding regular season. Additionally, seven of the 10 postseason champions between 2006 and 2015 ranked within that top seven.

But much like Pittsburgh, the Tampa Bay Lightning has never been known for faceoff prowess. The Bolts have made the conference final in 2004, 2011, 2015, 2016, 2018, and in 2020, and their rankings in faceoff percentage in those years were 15th, 16th, 16th, 20th, 27th, and 10th, respectively. The same can be said for the quasi-dynasty New Jersey Devils of the late 1990’s/early-200o’s who went to three Stanley Cup Finals between 2000 and 2003 with finishes of 16th, 18th, and 10th in faceoff success.

The good news for teams who struggle in the faceoff circle is that there has been at least one conference finalist in 12 of the last 13 years who finished in the bottom half of league rankings, including Vegas (16th) and the New York Islanders (17th) last season. Lastly, eight of those last 12 final fours had at least two squads who were ranked below average.

“Gotta get the power play going!”

Another common gripe we always hear is one that seems to grow more raucous towards the end of the season, and that is how poorly executed or pass-happy a team’s power play appears. Contrary to what some may lead you to believe, however, power-play goals on the scoreboard are worth no less than the tallies at even strength or shorthanded. And a paltry hit rate, as stark as it may seem on paper, can actually be contextualized into several positives.

In other words, not clicking on the power play doesn’t render an entire lineup ineffective. Nor does it accurately depict the quality or level of skill of the players on the ice. In fact, one can argue that simply earning the power play itself, usually via lengthy possessions inside the opposing end or from just plain hard work, can have positive second- and third-order effects on five-on-five play thereafter. Additionally, a suboptimal conversion rate on the power play doesn’t necessarily mean pucks aren’t moved effectively or high-danger attempts are passed up. No matter how you look at it, two minutes inside enemy territory while maintaining the initiative is still two minutes inside enemy territory while maintaining the initiative. Ten times out of ten, you’d rather have that power play and fail to convert than not have that power play and defend your own end.

Nonetheless, it’s quite rare that a pop-gun power play that struggled during the regular season ended up degenerating in the playoffs, thereby presenting critics with an easy target to explain the first-round ouster. A top-ranked unit getting smothered by an elite penalty kill or locked-in goalie? Ok, that makes more sense and probably lessens the blow by a hair. But getting bounced earlier than later generally has more to do with that hot goalie or even a disparity in talent, well before we can aim our anger on some carry-over issues from the three or four power-play chances per playoff game.

Therefore, it should come as no surprise that the data supports the idea that a strong regular-season power play is exclusive only to eventual Cup winners and conference finalists. Of the 160 teams who reached the final four since the NHL-WHA merger of 1979-80, 40 percent (64/160) ranked in the bottom half of the league in power-play efficiency, compared to only 53 percent (84/160) who placed in the top 10. Furthermore, between 2003 and 2017, nine of the 14 conference finals in that period involved at least three teams per postseason who ranked outside the top 10, including 11 Cup winners.

Lately, however, we’re starting to to a shift where the most high-powered units with the man advantage are heavily represented in the last three seasons worth of conference finals — eight of the 12 teams who made it into Round 3 in that period ran top-10 power plays, including each of the last three Cup champions (Tampa, St. Louis, and Washington). This trend used to be the norm between 1980 and 2002, when 19 of the 23 Stanley Cup winners (83 percent) owned one of the league’s top-10 power plays.

And he’s another interesting factoid regarding power plays and the Stanley Cup — between 1981 and 1996, the league’s No. 1 ranked unit took home the championship five times and made it as far as the conference finals in nine. This has changed quite a bit in recent years, however, as none of the last nine postseasons (2012-2020) had a top-rated power-play unit reach the conference finals, and Vancouver in 2011 and Detroit in 2009 as the lone representatives dating all the way to 2002.

FWIW, regular season PP ranks of last 10 Stanley Cup champions

2009 PIT 20th

2010 CHI 16th

2011 BOS 20th

2012 LA 17th

2013 CHI 19th

2014 LA 27th

2015 CHI 19th

2016 PIT 17th

2017 PIT 3rd

2018 WAS 7th— The Draft Analyst (@TheDraftAnalyst) February 11, 2019

“Home Cooking”

This isn’t going to another regurgitation on the insignificance of home-ice advantage in the Stanley Cup Playoffs, where higher-seeded hosts win about 55 percent of their series; a far cry from what is seen in the other three major sports. Instead, we’re going to focus on home records during the regular season, and if there’s any relation between home-ice success and deep runs into the third and fourth rounds.

Basically, the answer is yes — teams who either win the majority of their home games during the regular season or rank among the league leaders in that category have a significantly higher chance of reaching the conference finals. Again, we get that this is far from shocking — teams with gaudy records when playing in their own rink generally have the high point totals required to clinch higher seeds, thereby weakening their early playoff strength of schedule. Whether it’s a coincidence or not isn’t the point. It’s just a fact that the higher the points percentage at home, the greater the likelihood of hoisting the Stanley Cup.

The NHL switched from the old division playoff format to the NBA-style conference system beginning in 1993-94. In the 26 postseasons since, only one team to reach the conference finals — the 2016 San Jose Sharks — had a losing home record (18-20-3). That means 103 of the 104 conference finalists had winning records, and of those 103, 88 had a home points percentage of .600 or higher. As far as those Sharks are concerned, they represent only one of eight teams since 1994 with a sub-.600 home points percentage to reach the Stanley Cup Final, of which only two — the 1997 Red Wings (.598) and the aforementioned 2012 Kings (.598) — ended up claiming the actual trophy.

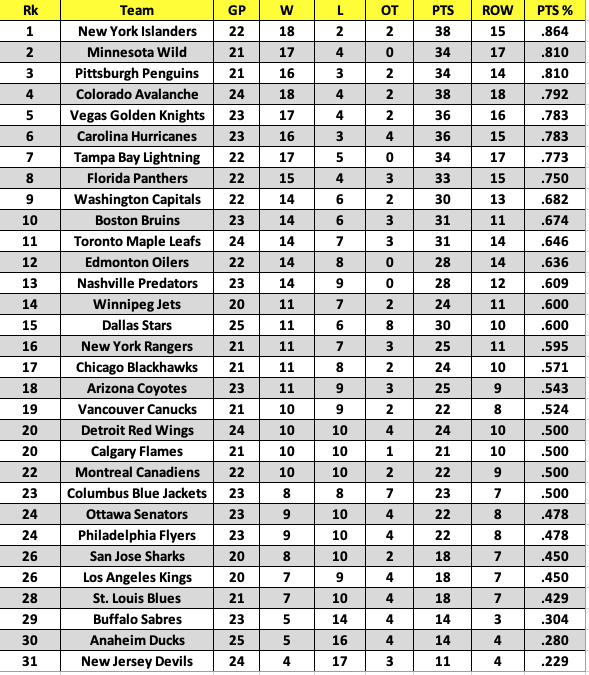

Of course, it’s totally fair to say near season’s end that mediocre teams with a home success rate south of .600 are more concerned with making the playoffs than winning the whole thing. But parity in the NHL definitely exists, especially during this shortened season that has nearly a dozen teams who either consider themselves contenders or are pretty close to it. So for their sake, it bears reminding that eighty eight of the last 104 conference finalists posted a home points percentage of .600 or higher, and the league average since 1994 for one of its final four teams is .676, with 19 of the last 26 Cup winners finishing with a .670 mark or better. As of Monday, almost half the teams in the league were at or above the .600 mark (see below)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!